(Re-)understanding Antenatal Care and Men’s Participation in Eastern Zimbabwe

Dr. Anthony Musiwa presenting a talk titled, "(Re-)understanding Antenatal Care and Men’s Participation in Eastern Zimbabwe," for the Global Health Seminar Series on Tuesday February 20, 2024. Blog Post written by Global Health MSc Student Saron Teferra

On February 20, 2024, Anthony Musiwa presented in a Global Health Seminar titled: (Re-) understanding Antenatal Care and Men’s Participation in Eastern Zimbabwe. “I put ‘Re’-understanding [antenatal care] because…I’m trying to weave in new perspectives to what we already know about antenatal care and men’s participation in rural eastern Zimbabwe” explained Musiwa, a Banting Post-Doctoral Fellow in the Department of Health Services Research, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University. Throughout his presentation, Musiwa illuminated the nuanced conceptions of antenatal care in global health, while drawing insights from his ongoing post-doctoral work in the Mafararikwa community in Manicaland province in Zimbabwe (Ward 16).

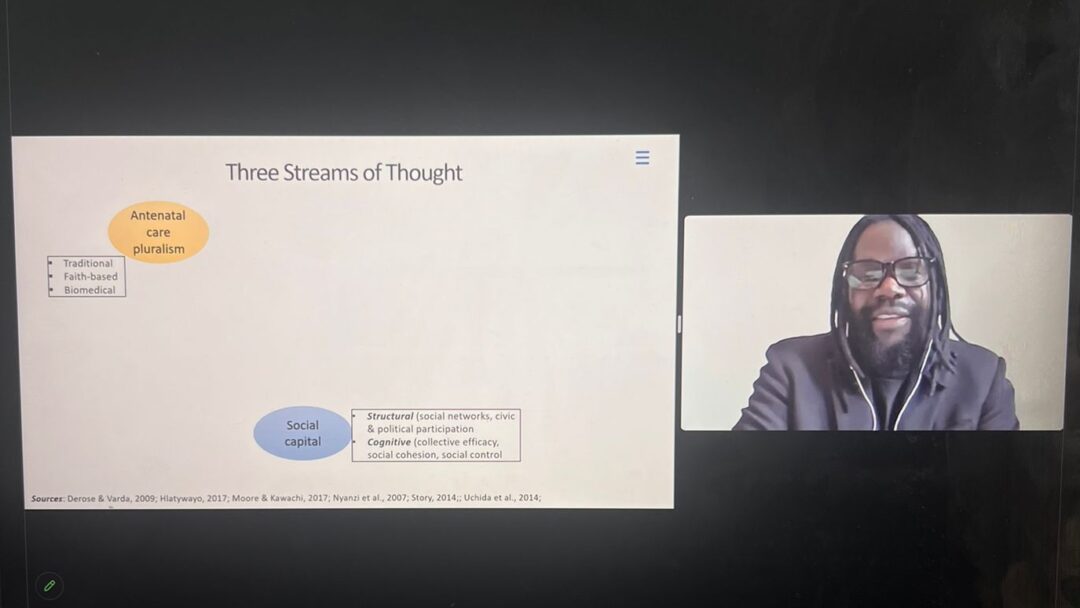

To re-understand men’s involvement and participation in antenatal care, Musiwa described how his research brings together what he refers to as “three streams of thought”. The first stream was centered on the pluralistic nature of antenatal care in Zimbabwe and many sub-Saharan African contexts, where families equally recognize biomedical, traditional, and faith-based antenatal care systems. Secondly, Musiwa’s research incorporates social capital, a term used to refer to the different forms of support provided when navigating antenatal care. Lastly, he stressed that antenatal care and social capital must be considered within the cultural context of where the research takes place.

Although the importance of social capital in health-facility-based antenatal care has been recognized since the mid-90s, there are few studies focused on sub-Saharan Africa. The few that do exist have mixed results but indicate the importance of context in outlining social capital and antenatal care access. When further exploring the limitations of existing literature, predominately grounded in biomedical frameworks, Musiwa stated that “when we have that kind of bias [towards biomedical systems], we are blind to other conceptions of antenatal care, other conceptions of social capital, and by extension–other conceptions of men’s participation”.

To further support his discussion on the importance of contextual and cultural understanding, Musiwa goes on to describe how he intentionally chose an African philosophical and theoretical framework of Ubuntu and specifically, Afro-communitarianism. These African frameworks centre the ‘WE’—actions that bring about the collective good and highlight nurturing relationships, and the harmonious, expansive, and interactive elements of community.

Musiwa went on to discuss his findings from in-depth interviews, consultations, storyboards, and focus groups with antenatal care stakeholders in Mafararikwa. Notably, most families in this locale accept multiple systems of antenatal care (i.e., traditional, faith-based, and biomedical). To navigate these services and systems, families frequently leverage social networks that provide material and non-material support such as food, money, moral support etc. Musiwa also explained that the most salient forms of social capital came through reciprocal actions and relationships. Participants expressed that it was meaningful knowing that they had reciprocal relationships whereby “I helped them yesterday, [so] tomorrow they will help me”.

In his research, Musiwa also found mutual trust to be instrumental in navigating antenatal care. Having an antenatal care provider with a pre-established relationship and mutual trust is especially important when considering the cultural and spiritual dimensions of pregnancy which include conceptions of life, family, and lineage. Musiwa also noted that many social networks contained antenatal care providers and gave the example of a grandmother who was a traditional midwife that provided care for people within her community.

In (re-) understanding men’s participation in rural eastern Zimbabwe, Musiwa’s research steps away from strictly biomedical understandings of pregnancy and the instrumental psychosocial role of men. Rather, it aims to support holistic and context specific perspectives of antenatal care by including social fathers and nuanced conceptions of social care and participation. In such contexts, men’s participation is not limited to biomedical antenatal care systems and may encompass spiritual care, love, support, and other practices often overlooked in biomedical research. On that basis, we must recognize that providing culturally appropriate antenatal care requires holistic consideration of community preferences and conceptions of social capital and antenatal care. This takeaway is further emphasized by Musiwa’s concluding statement, which underscored the importance of meeting “families where they are at in order for us to develop culturally appropriate efforts to strengthen informal support systems.”

Student Blog

Related News

News Listing

November 12, 2024

November 5, 2024

Pollution, Power, and Protest: Unpacking Environmental Racism from Africville to Wet’suwet’en

Student Blog

October 10, 2024